You’ve heard from many sides, different accounts of how the Obama campaign used „Big Data“ to „win the election.“ However, no one knows better about it, than the guy responsible for it all: Ethan Roeder was Director of Data from Summer of 2011 till Election Day. After the election, he visited Vienna to talk about Truths and Myths behind the campaign’s data operation. He was friendly enough to summarize his talk in a guest post. For those even more interested: He also wrote a piece titled „I’m Not Big Brother“ for the NYT. Take it away:

Ethan Roeder: The role of Data on the Obama Re-Elect

On Election Day, 2012, the Obama campaign had 107 dedicated, full-time data staffers in 19 states. Eight months earlier, however, our position was not so strong. In March, 2012, our data team numbered about 30 and we had already hired practically everyone on the market who had prior political data experience. Summer was approaching and with it an aggressive ramp-up of our program and staffing. We were going to need dozens of additional skilled practitioners; where were they going to come from?

After weighing our options we decided to leverage our email list and network of young supporters to identify prospects. If we were going to build an army of data staff, we realized, we would need to find new recruits and put them through boot camp. We designed a five-week online course that ultimately transformed a select group- drawn from over 2,000 applicants- into some of the most effective data staffers to ever work in politics.

Of the challenges we faced in building and executing this ambitious recruitment program, one was unexpectedly vexing: what do we call it? This question was so low on our list of concerns that it rarely even registered. But when the time came to secure the approval we needed to publicize it, this remained the one sticking point above all others; one so tenacious that Campaign Manager Jim Messina was called upon to resolve it. We joked at the time that it was only a matter of time before POTUS would weigh in.

Our internal working-title for the program was “Data Academy.” We weren’t going to score high points for creativity with that one, but at least it got the point across. Attend this thing and learn data stuff. How could such an innocuous name possibly stir the discomfort of campaign leadership? Answer: it contained the word “data.” And data is scary.

We settled on “Field Tech Academy.” Despite the linguistic gymnastics we were very pleased with the outcome of the program: we were able to recruit and train a diverse, talented, and highly-motivated new class of practitioners.

Naming the Field Tech Academy captures the confusing consequences of working on something new in politics. Our campaign team was doing exactly what they were being paid to do- steering clear of a distraction that bore no relevance to the banner issues of the campaign. Yet this policy of deflection led to distractions of its own: open speculation. Before long we were supposedly encouraging our supporters to spy on their neighbors and monitoring the porn consumption of voters. By declining to offer a narrative of our own we created an opening for everyone with curiosity and a keyboard to sort out for themselves what must be going on in the infamous “cave.”

Of course the speculation wasn’t only negative. Some of the awed accounts of our game-changing accomplishments were just as detached from reality as the conspiracy theories. Obama didn’t win because of new technology and his campaign didn’t contact 40% of the American population. Obama won because he was the better candidate. Data, Analytics, and Technology served the President in his effort to connect with and motivate voters. You can’t turn a turd into a victor using some brains in a back room.

What follows is a crack at the reality of what Team Data did- and did not do- on the Obama re-election.

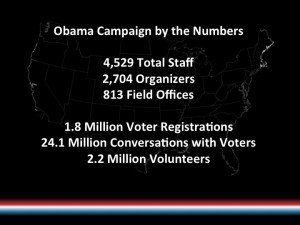

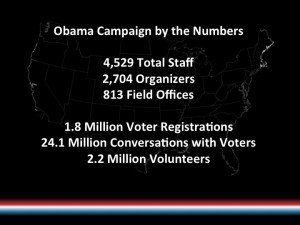

By Election Day, the Obama campaign had over 4,000 paid, full-time staff. Most of them were Field Organizers working out of over 800 offices in key battleground states. By comparison, the Romney campaign had fewer than 300 field offices. The Obama approach to data cannot be separated from our commitment to investing in field.

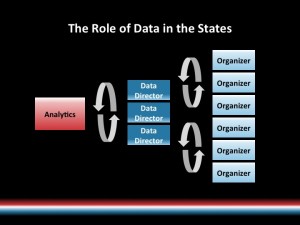

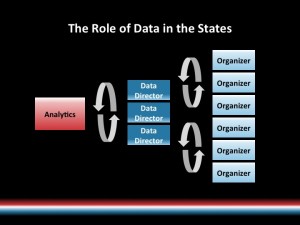

Staffing in a typical state included a Data Director and a number of Deputy Data Directors. In a large state such as Ohio, deputies may have been responsible for specific program components such as daily progress reports, early vote data, polling location data, data trainings, mapping or in-state tech development.

While these staffing levels are obviously unattainable without significant resources, it’s far from assured that a large campaign would invest in this way. Data resources are a force multiplier. Our campaign was able to make more efficient and effective use of our resources because of our deliberate effort to staff our data program adequately. Any campaign has to deal with limited resources and the payoff for investing in data, even to a modest degree, is a bigger return on all the rest of the campaign’s efforts. Data is a turbo booster for campaigns.

One way to think of the Data team is as the bridge between the strategic intelligence our Analytics team provides and implementation on the ground. A data director works with other members of the state leadership team to determine program goals- the most obvious of these being how many votes are needed to win. The next step is calculating capacity- how many volunteers have been recruited, how many more can be recruited in the lead up to the election, and how many voters can be contacted total? Once that strategic groundwork has been laid the final step is using voter contact models to determine the final lists our field organizers will work from.

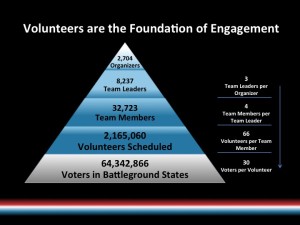

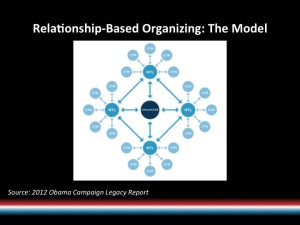

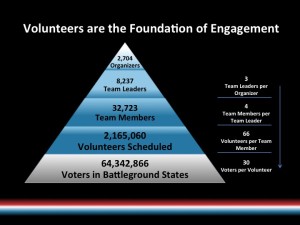

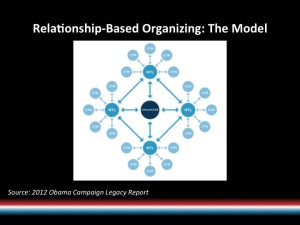

The campaign identified and trained over 8,000 volunteer “Neighborhood Team Leaders.” These volunteers would assume responsibility for organizing their own neighborhoods and recruiting other volunteers to help deliver their area for Obama. These NTLs worked with an assigned Field Organizer (a paid staffer) and were given target goals, progress reports, and volunteer prospect and voter lists to help them achieve their goals. They were respected as formal member of our campaign team and were given access to data and held accountable to goals.

By training volunteers to take on leadership roles and by holding them accountable to firm goals we were able to expand the reach of our campaign. This organizing model, also known as the “snowflake” model, can be used by any campaign large or small to turn the excitement about a campaign into productive action on the ground.

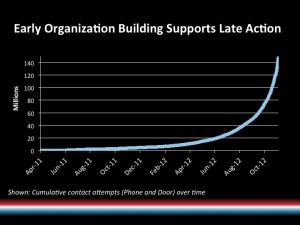

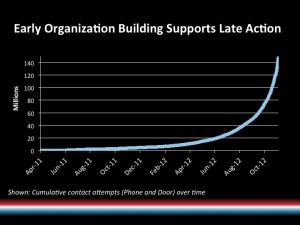

Campaigns interested in using relationship-based organizing to build strength on the ground must commit early resources to organization building. This presents some challenges for a campaign. First, staff hours that might otherwise be directed towards more immediate and tangible activities (such as voter contact) must be reserved for the time-consuming activities required to recruit and build relationships with volunteer leaders, train them, and manage them. Second, it can be difficult to build excitement and urgency when election day is in the distant future. When these challenges are met and overcome, however, the payoff is enormous. From the 2012 Obama Campaign Legacy Report: “On November 6, 2012, the last day of voting in the most important election of our lives, more than 100,000 Obama for America canvassers knocked on more than 7 million doors and twice as many volunteers called voters to make sure they got to the polls.”

A detailed accounting of the principles of this approach to organization-building can be found in the excellent publication from the New Organizing Institute- Campaigning to Engage and Win: A Guide to Leading Electoral Campaigns.

By the summer of 2012 our ground effort was in full swing. Our organizers and volunteers were encouraged to tell their own stories- why are they giving up their Saturday afternoon to make calls for the President? What issues personally resonated with our volunteers and motivated them to get involved? This helped drive more engaging conversations and encouraged our team to build relationships with voters- not just deliver talking points.

Cold-calling is never easy, but it’s the currency of engagement. The American electorate is more culturally heterogeneous now than it has ever been and having a conversation with a family of first and second-generation immigrants from the Middle-East is not likely to bear much resemblance to a conversation with a White college Freshman with centuries of roots in the country. These cultural considerations are no reason not to engage voters directly. On the contrary these diverse backgrounds are the fuel that gives shape and purpose to political engagement.

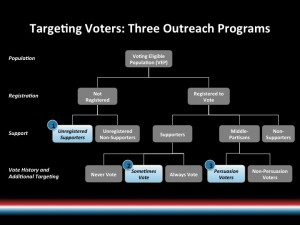

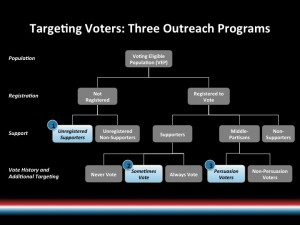

There are three reasons a campaign would expend resources on a voter: to register them to vote, to persuade them to vote for our candidate, and to mobilize them to cast a ballot. From top to bottom, our Tech, Data, Analytics, and Field operations were all designed to define these segments, identify target areas or individuals, and execute the appropriate program based on our intelligence. Much of the conversation about political campaigns often revolves around “independent” or “swing” voters, but persuasion is just one element of a winning campaign.

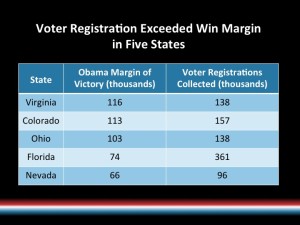

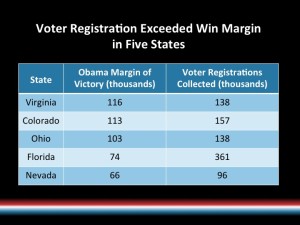

The path to victory is different for each state. In a state like Michigan, working to increase Democratic turnout can be enough to carry the state for a Democratic candidate. In a state like Florida, however, we needed to run aggressive programs to register new voters, persuade, and turnout in order to win.

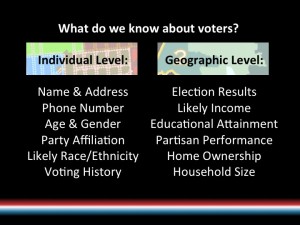

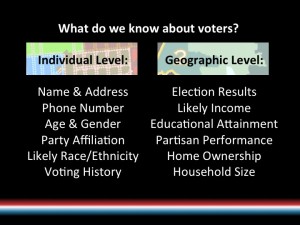

Our efforts to identify who we should target were only as good as the data we started with. In the US, publically-available voter files contain much of the information campaigns need to start targeting. The cost, format, and availability of voter files varies from state to state. Individual-level information from these voter files was supplemented with our internal finance and volunteer databases and consumer data vendors. This was then combined with geographic-level information from the US Census to establish a high-confidence profile of targeted precincts and individuals.

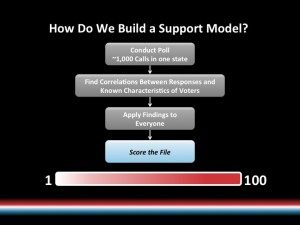

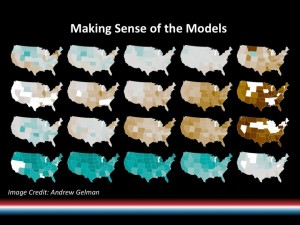

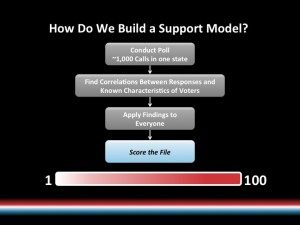

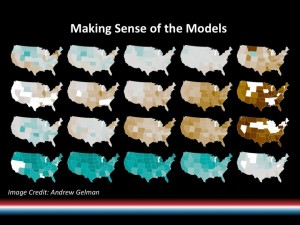

Our analytics team used the combination of individual and geographic-level data to build statistical models. We call these “voter contact models.” A model is essentially an opinion poll that has been extrapolated to the individual level. These models helped us identify our target segments: voters who would be likely to support Obama, for instance, and might fit into our turnout program. These models were added to individual voter records as a “score” between 1-100.

For more on how the Obama campaign built and used statistical models, the LA Times has a good overview in this article and journalist Sasha Issenberg has an in-depth, three part series here.

A voter contact model is just a tool- it can be interpreted and used in many different ways. Our Data Directors worked with other members of the state leadership team to determine how to implement these models. Do we want to focus more of our resources on turnout or persuasion? What about voter registration? How many volunteer hours do we think we can count on over the summer? How many actual conversations with voters can we have? The result of these calculations was our voter contact list.

Data doesn’t end at voter files and statistical models.

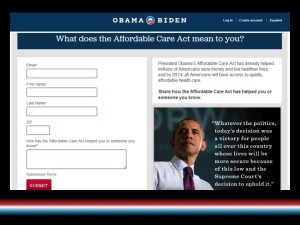

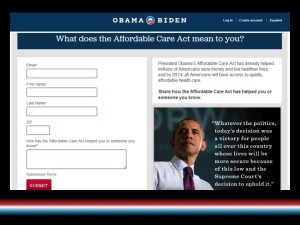

This video, produced in-house by the Obama campaign, tells the story of Stacy Lihn and her family. Her daughter was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect and, despite having health insurance, was already halfway to her “lifetime limit” at the age of six months. The Affordable Care Act eliminated those lifetime limits.

Stacy shared her story with the Obama campaign by way of an online form. Hers was one of thousands of stories collected not only through this form but also shared with organizers and volunteers in conversations all over the country. Because the campaign was looking for these stories, because these stories were important, and because we had the tools to search through them and make sense of them, we were able to make the Lihn family a part of the narrative fabric of the campaign.

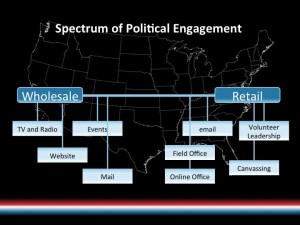

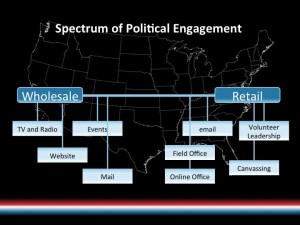

Campaign activities can be thought of as existing on a spectrum from more wholesale to more personal, or “retail.” At one end of the spectrum are mass-marketed approaches to campaigning: TV ads, large events, traditional websites. Things get more personalized with more targeted approaches- local campaign offices, targeted mail and email campaigns, and, at the far end of the spectrum, building relationships with individual voters and empowering volunteers with leadership roles within the campaign structure.

The terrain of political engagement isn’t flat, however. Campaigns make deliberate decisions about how to structure their outreach and this naturally has consequences for the nature of the relationship voters have with the campaign. When a voter calls a campaign office to ask a question, or when they indicate they are interested in a particular issue on a web form, are they dispensed a position paper or do they get a call back from an organizer? Are they invited to come to an office opening or an event or do they simply get to enjoy the promise of dozens of fundraising emails?

No campaign needs a billion dollars to engage voters, to ask them for their story, to engage them as a whole person. Any campaign can build a Data program that values the qualitative over the quantitative, that values interpreting information over amassing it, and that empowers local staff and volunteers to solve problems and engage voters using their own guile.